Why Do We Have Bank Holidays? Their History and Origin

This is it folks. The definitive guide to UK bank holidays. What they are, why we have them, the history of bank holidays etc. etc.. The whole kit and caboodle.

What is a Bank Holiday?

The definition of a bank holiday is “a weekday on which banks are closed by law; legal holiday”.

The term is used in the UK, its former territories, and a small handful of other European countries, and while both ‘bank holiday’ and ‘public holiday’ can both be days off and used interchangeably there is a technical difference: a ‘bank holiday’ is derived from statute law and a ‘public holiday’ is derived from common law.

To you, me and the next man though there’s no difference. Whichever term is used may only really matter in academia and perhaps the banking and legal professions.

However, before we begin, an important point needs to be made: that of whether you can take a day off work, or not. This depends on your contract with your employer. It is not an automatic right. Find out if you can take a day off on a bank holiday.

The History of Bank (Public) Holidays

In the UK ‘bank’ or ‘public’ holidays have become a highlight of the calendar year evolving over centuries of cultural and political change, and a combination of tradition, religion, days of historic significance, legislation, and a more practical approach to work and life.

Some holidays may seem obvious: Easter and Christmas for example are important (pre-)Christian festivals. Others may seem a little more esoteric and you may wonder why we have an Early May or late August Bank Holiday, but no public holidays in England and Wales on the patron saint’s days?

Well, read on …

In the days of yore when Britain was largely an agricultural economy and less urbanised life revolved very much around the family, village, farm, and seasons. People celebrated the natural cycle of life such as the end of winter, the coming of summer, the summer solstice, and harvests. They prayed for a bounteous crop and were genuinely thankful when it happened.

Livelihoods depended on the seasons and the prospect of a poor harvest, flood, long winter, or wet summer was potentially disastrous. As such the arrival and passing of these important times of year were significant dates in the agricultural calendar and people’s lives, and festivals became a customary way to mark them. As such many northern European countries share similar traditions and festivals at similar times of year.

Many traditions are in fact pagan or pre-Christian in origin but as Christianity spread throughout the kingdom it wasn’t long before new, religious festivals began to merge with existing traditional festivals, or develop anew around the Christian calendar.

Work was hard in the early nineteenth century – really hard – usually manual whether in a factory, mill or on the land, and people worked long hours. But they did take holidays – not quite in the same fashion we do today (two weeks holiday would have been unheard of, and foreign holidays were reserved only for the wealthy) but they tended to be religious, seasonal and often localised, and spread throughout the year.

Pretty much the only nationwide days off people had were Sundays, Good Friday and Christmas Day.

In fact the word ‘holiday’ itself derives from it being a holy day. As the Online Etymology Dictionary defines it a holiday is:

1500s, earlier haliday (c. 1200), from Old English haligdæg “holy day, consecrated day, religious anniversary; Sabbath,” from halig “holy” (see holy) +dæg “day” (see day); in 14c. meaning both “religious festival” and “day of exemption from labor and recreation,” but pronunciation and sense diverged 16c.

According to Wikipedia and Wikisource by 1834 the Bank of England observed around 33 saints’ days and religious festivals as holidays, but reduced these to just four in 1834: 1 May (May Day), 1 November (All Saints Day), Good Friday, and Christmas Day. Similarly the Encyclopaedia Britannica states that “Before 1830 the Bank of England closed on approximately 40 saints’ days and anniversaries, but that year the number was reduced to 18 days.”

Given the casual approach to research most other sources have adopted the inference here is that the rest of the country also followed suit and took time off at the same time as the Bank of England. There is little evidence to support this though, as H. Cunningham points out below, as these holidays were confined to the Bank and not explicitly stated to refer to the general population as well.

In The Cambridge Social History of Britain, 1750-1950, H. Cunningham says “There may have been a reduction in holiday time in the early nineteenth century, though the evidence on which this is based is confined to the Bank of England which closed on 44 days in 1808 and on only four in 1834. By 1845, however, the trend had been reversed and Bank workers were getting six to eighteen days’ annual leave …”

Whether the general populace also had a holiday at the same time is unclear as official legislation on nationwide holidays wouldn’t exist for another 37 years until the passing of the Bank Holidays Act 1871.

In addition, with such a yo-yoing in the number of holidays the Bank took, it seems quite plausible that it would be difficult for businesses across the country to follow suit.

H. Cunningham continues: “Regional variations were of crucial importance in the evolution of holiday habits. In most parts of the country holidays had always been considered as particular days rather than as a stretch of days. Such holidays were the most vulnerable; they could be picked off one by one, especially in areas where labour organisation was weak …”

It wasn’t until 1871 that ‘bank holidays’ for the whole country were officially recognised in law as a nationwide holiday as you’ll see below.

Bank Holidays Act 1871

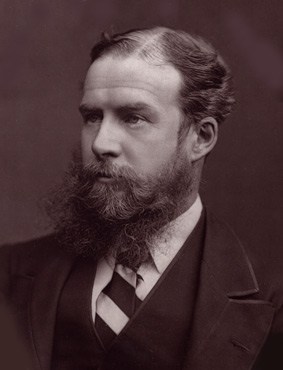

Bank holidays only came into existence in 1871 when the banker-turned-politician Sir John Lubbock, the first Lord Avebury, introduced the Bank Holidays Act.

According to Horace G. Hutchinson in the Life of Sir John Lubbock, Lord Avebury, Volume 1, his political aims were threefold:

- To promote the study of Science, both in Secondary and Primary Schools

- To quicken the repayment of the National Debt

- To secure some additional holidays, and to shorten the hours of labour in shops

So popular was he, as Hutchinson continues, that the Daily Telegraph suggested naming the August holiday “St. Lubbock’s Day”. Bell’s Life exclaimed “A Statute Holiday! A holiday by Act of Parliament!”

The News of the World was head over heels about him: “Blessings on the head of Sir John Lubbock, who invented a decent excuse for holidays to Englishmen. We never wished for a revival of Saint’s days, but we certainly did wish that some great inventive genius could discover a reason why the people should not work all the year round, Sundays, Good Fridays, and Christmas days excepted … Sir John has shown of himself to be an inventor of the highest order, and his great reputation as a man of science has been enhanced by the invention of Bank Holidays.”

As for why they might be called ‘bank holidays’ Doug Pyper explains in the House of Commons’ Briefing Paper, December 2015, on Bank and Public Holidays: “while most employers were able to give their workers days off on “public” holidays, it was difficult for banks to do so because the holders of bills of exchange had the power to require payment on those days”.

Quoting the Parliamentary Debates, 3rd Series, Vol. 206, 4 May 1871, he continues:

“The question of holidays was generally left to be settled between employers and employed, and it was very easy for most employers who desired it, to give their men a holiday at a small pecuniary sacrifice to themselves; but that was impossible in the case of banks so long as the holders of bills of exchange and promissory notes had power to require payment on those days. In order to avoid bankruptcy it was necessary that banks should be kept open on those days, and thus the clerks could not have holidays on – such occasions. He believed a feeling was generally growing that work in England was quite hard enough, and that additional holidays would not be unwelcome to those to whom they were given, nor unpopular with the general community.”

When legislation was drawn up an important part included that “no person was compelled to make any payment or to do any act upon a bank holiday which he would not be compelled to do or make on Christmas Day or Good Friday, and the making of a payment or the doing of an act on the following day was equivalent to doing it on the holiday.” This basically meant that everyone was entitled to time off.

The bank holidays introduced were:

| England, Wales & Ireland | Scotland |

|---|---|

| New Year’s Day* | |

| Easter Monday | Good Friday |

| Whit Monday | First Monday in May |

| First Monday in August | First Monday in August |

| Boxing Day/St. Stephen’s Day | Christmas Day* |

* If Christmas Day and New Year’s Day fall on a Sunday, the following Monday is the bank holiday

An Act of 1875 later proclaimed 27 December to be a holiday in England, Wales and Ireland when 26 December falls on a Sunday, i.e. the first weekday after Christmas, Boxing Day.

To quote Wikipedia “The Act did not include Good Friday and Christmas Day as bank holidays in England, Wales, or Ireland because they were already recognised as common law holidays: they had been customary holidays since before records began.”

Later on in 1903 the Bank Holiday (Ireland) Act added 17 March, Saint Patrick’s Day, as a bank holiday for Ireland only. It’s included here as Ireland was then part of the UK and Northern Ireland retained the holiday after Irish independence.

Banking and Financial Dealings Act 1971

Commencing in 1965, stemming from a White Paper on Staggered Holidays, and on an experimental basis, the government proposed to change the Whit May bank holiday and August bank holiday upon “a general desire that everything possible should be done to alleviate the growing congestion at the peak of the holiday season.”

“Our further consultations have confirmed the view that a fixed Spring Bank Holiday and a later August Bank Holiday could make a worthwhile contribution to the extension of the holiday season and to the avoidance of congestion for holidaymakers at peak holiday times. The Government have, therefore, decided, after full consultation with the interests concerned, that the August Bank Holiday for the next two years, 1965 and 1966, should be on the last Monday in August. The Government would have wished to combine this experiment of moving the August Bank Holiday to the end of the month with a fixed spring holiday on the last Monday in May, 1965 and 1966, to replace the present Whit Monday Bank Holiday. This is not possible in 1965 because of the arrangements which have already been made for school examinations. These cannot now be changed without serious inconvenience. In 1966 the Whit Monday Bank Holiday will in any case fall on the last Monday in May.”

Upon the success of the trial the next official overhaul came in 1971 with a revision to the 1871 Act.

The new 1971 Banking and Financial Dealings Act was incorporated therefore and moved the August Bank Holiday from the first Monday to the last, and the Whitsun holiday to the last Monday in May.

Further revisions included New Year’s Day being proclaimed a bank holiday in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in 1974, the first Monday in May (excl. Scotland) in 1978, and the final Monday of May (Scotland) were designated as bank holidays.

In January 2007, the St. Andrew’s Day Bank Holiday (Scotland) Act 2007 was given royal assent, making 30 November (or the nearest Monday if a weekend) a bank holiday in Scotland but banks and other organisations are not compelled to take it.

Royal Proclamations

The 1971 Act also gives Her Majesty the power to appoint additional days as bank holidays by Royal Proclamation. This basically means if a bank holiday falls on a weekend she legislates for the following Monday to be the bank holiday instead (if not already stated in law).

There are a few instances when holidays were added or subtracted such as the Queen’s Silver Jubilee in 1977 but the definitive list of bank holidays is below.

The Definitive List of UK Bank Holidays

By 1978 the land lay as follows with eight holidays a year in England and Wales, nine in Scotland and ten in Northern Ireland:

| England & Wales | Scotland | N. Ireland |

|---|---|---|

| New Year’s Day (2) | New Year’s Day (1) | New Year’s Day (2) |

| 2 January (1) | ||

| St. Patrick’s Day, 17 March (4) | ||

| Good Friday (3) | Good Friday (1) | Good Friday (3) |

| Easter Monday (1) | Easter Monday (1) | |

| First Monday in May (2) | First Monday in May (2) | First Monday in May (2) |

| Last Monday in May (1) | Last Monday in May (1) | Last Monday in May (1) |

| Battle of the Boyne, Orangemen’s Day, 12 July | ||

| First Monday in August (1) | ||

| Last Monday in August (1) | Last Monday in August (1) | |

| St Andrew’s Day, 30 November (1) | ||

| Christmas Day (3) | Christmas Day (1) | Christmas Day (3) |

| Boxing Day (1) | Boxing Day (1) | Boxing Day (1) |

Notes:

1) Banking and Financial Dealings Act 1971

2) Royal Proclamation under 1971 Act

3) Common law public holiday

4) Proclaimed by Secretary of State for Northern Ireland